Making the Most of spaCy's Rule-Based Matcher

TL;DR

The Rule-Based Matcher in spaCy is awesome when you have small datasets, need to explain your algorithm, locate specific language patterns within a document, favor performance and speed, and you’re comfortable with the token attributes needed to write rules. I created a notebook runnable in binder with a worked example on a dataset of product reviews from Amazon that replicates a workflow I successfully used on a recent project.

Overview

Recently I’ve been spending time with spaCy’s Rule-Based Matcher for a client project. I’ve found it really helpful for our particular case, where we have a small dataset of about 2000 text narratives that document different aspects of a recurring business process meeting. Within the text, we’re looking to identify any issues that might have been documented in the narrative, but not documented in any structured data, and bring them to management’s attention.

All the usual tricks were attempted on this data to try and extract something useful: topic modeling (LDA, Embeddings>UMAP>DBSCAN), supervised learning, even labeling thousands of narratives. None of them panned out with anything helpful, mostly due to the size and diversity of the dataset. However, as I was labeling data, I took notes on patterns I was seeing in the data. These patterns were then used to start making rules to surface issues from patterns in the text. As a plus, we are able to explain what the rules do and how they work to stakeholders; some are even simple enough that the stakeholders have provided feedback and ideas to expand the rules.

I’m assuming that the rule-based matcher is an underused or unknown tool in many practitioner’s NLP toolboxes. It might not be as “cool” as a machine learning approach (though you’ll still training models with my workflow) and requires some linguistics knowledge. Also, in the spaCy ecosystem, it’s a tool I found difficult to make useful in isolation. Rather, the power comes from combining matches with a specific match callback for your problem, extension attributes, and taking advantage of training some pragmatic models to improve your match rules.

Advantages and Challenges of Rule-Based Matching

✅ Why rule-based matching is awesome ✅

- No training data required (good for smaller datasets)

- Match results give you flexibility for returning relevant sections from your document.

- i.e. document classification works on whole documents. What if you wanted to find a sentence or phras that was relevant to your problem? The matcher allows you to work with specific sentences and spans after matching.

- It’s Fast!

- Easy to integrate into an NLP pipeline

- Composable and cheap

- e.g. you could write a bunch of quick, simple rules and use boolean logic on the matches to interesting match combinations.

- e.g. you can write a really general rule to find relevant documents, then some mutually exclusive sub-rules that operate only on documents that match a general rule.

- Usually explainable to non-technical stakeholders

⚠️ Why rule-based matching is challenging ⚠️

- Good rules require lots of iteration and experimentation

- Writing rules requires some linguistics knowledge about parts-of-speech and dependency parsing

- Token matching operators are greedy

- Requires frequent sanity checking, testing, and iterating to be sure the matcher is returning what you think it is

- Requires complementary tools for maximum benefit

- You’ll probably want to use an

on_matchcallback to work with the full document or a span after a match. Often times the match itself is just the start. - We train a text classification model on our matches to help us iterate. I found parameter tuning difficult and training very fragile due to the rare outcome rate for matches.

- You’ll probably want to use an

The Workflow

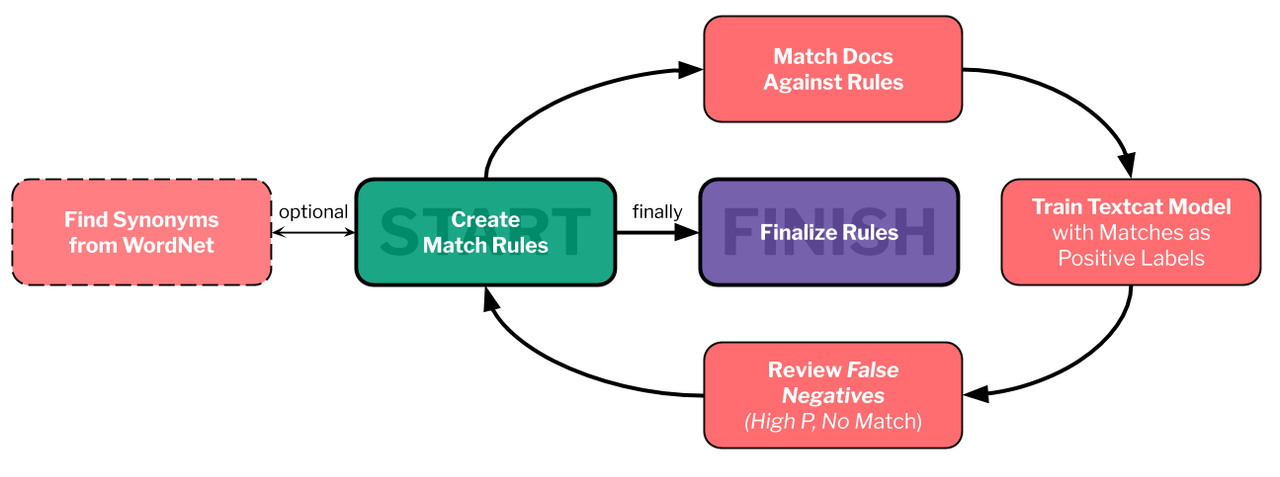

Here’s the iterative workflow that I developed to solve these types of problems. The steps are:

- Create Match Rules. Developing a rule is a way to answer to the following questions: “What is the information I want?”, “How would people write about this information?”, “What attributes on tokens exist to help match the information I want?”. Your answer to the last question may just be the tokens themselves - in my example, we don’t use any advanced token attributes for our first rule, just the lowercase token. For more complex attributes, you might want to put some examples into the displaCy visualizer. It can be helpful to identify a single example from your dataset that you would want to match. From here, write your first rule. Then, think of variations in how people would write about the information you want. I use WordNet and synonyms in my example, but you could also used a pretrained word embedding model to identify synonyms.

- Match Docs Against Rules. Here you use the matcher to identify documents with matches and store those matches on a custom attribute of that object. This allows you to identify which documents have a match and what that match is. You will want to sanity check your match at this point to verify if it’s capturing what you want.

- Train a Text Classification Model. Here we’re borrowing from an idea referred to as weak supervision. We’re going to treat all our documents as if we labeled them and our matched documents as if they have a positive label. The idea here is that a trained model will pick up on other patterns of the text that our rules missed. After training, we predict this label on all of our documents. Then, by treating the matched documents as actual labels, we will inspect potential False Negatives from the model predictions.

- Review False Negatives Filter and sort the documents so that they include documents that did not have matches but have high predicted probabilities. These documents should have language similar to documents that were matched, but you don’t have rules for so they weren’t captured. You’ll need to manually review these and consider again some of the same ideas you thought about in step 1 when originally creating the rules. At this stage, I usually take notes into 3 categories: Rule Additions for things I want to add a rule for, Noted Exclusions for patterns that might be what we’re looking for, but we’ll ignore for this iteration, and Other Ideas for things I thought of while reviewing.

- Repeat or Finalize Rules. Either repeat steps 2-4 with your new match rules, or finalize the rules you want to match on.

Examples Please

This is the use case I cover in the notebook.

Let’s say we work at Amazon, and our boss wants us to explore a potential a new feature for product pages: a list of reasons why people purchased that item. If we assume people write things like

I bought this because my old whisk brokein their reviews, we could use the text from product reviews to initially build this feature.

Using this workflow, we have a process for automatically extracting these patterns from reviews. As an example, using reviews from a coffee grinder, everything after “Customers by this product …” below was extracted automatically with the matcher.

Customers buy this product ...

... as a replacement for a Salton model.

... as a Christmas gift for my son in law.

... as a new coffee maker for serving guests of an annual retreat we host in our home.

... as a spice grinder and are very happy.

... as a christmas gift for a friend and it works great.

... as a spice grinder and a coffee grinder

... because it was cheap and had good reviews, and I have not been disappointed.

... because of the excellent reviews.

... for grinding dry spices.

... for grinding coffee

... to grind beans for cold-brewed coffee.

... to grind spices instead of coffee and it works great.

... to grind xylitol and truvia sweeteners into a powder for cooking.

Wrap Up

This workflow was the perfect fit for me on a project where I had smaller data, a vague prompt for entering text, and specific language patterns I wanted to extract from text. The pipeline really started to provide value once I understood how all the tools I had available worked together and developed a consistent workflow around them. Next time you’re tackling a problem that has similar constraints or you want to give a new tool a shot, don’t hesitate to reach for the rule-based matcher.